THERE has been much talk and discussion recently in the press and on the web about future prospects for a new cinema version of Epic Mahābhārata. I would like to add a few professional words to this ongoing dialogue. The Mahābhārata describes a world of heroes who are neither mortal nor divine but who oscillate

THERE has been much talk and discussion recently in the press and on the web about future prospects for a new cinema version of Epic Mahābhārata. I would like to add a few professional words to this ongoing

dialogue.

The Mahābhārata describes a world of heroes who are neither mortal nor divine but who oscillate between both these worlds; each hero being typically connected with one particular deity, either genetically or characteristically. Epic was originally a kṣatriya literature in which heroes struggle to overcome the void of death by gaining kīrti, ‘fame’, something which transcends all destruction. Fame refers to the imperishable medium of epic song; in our case today, this will be replaced by immortal cinema.

Death is the one heroic aim in life, that is their active counterpoint: for in order to become immortal, heroes must die. Death in the epic is aestheticised into something beautiful, in fact the word ‘he dies’ is rarely used and metaphor replaces that expression. Typically, heroes are likened to trees, this is a key image for their likeness: beautiful trees in blossom, for death is seen as something exquisite and profoundly fertile. Other conventional imagery concerns fire, the blazing and the sacrificial; or mountains, the immoveable and invulnerable. Heroes live and die according to a strict code of warrior conduct. Often this leads to conflict between a hero and a king: one who possesses status and one who possesses power. This system of rules governs not only martial accomplishment but also fidelity and true speech: the formal protocols of boasting and the integrity of verbal allegiance, for the probity of a hero’s speech and language is as crucial as his martial abilities. Guest relationships are important (taking salt), as is loyalty to one’s patron (Karṇa and Duryodhana). Friendship is similarly not to be betrayed: male amity between heroes is intimate and inviolable, second only to the father-son relation, which, among heroes is more important than any other kinship involvement. The model of amity as exhibited between Arjuna and Kṛṣṇa being the highest exemplum of this. Epic society demonstrates a highly ranked and integrated form of culture where personal fealty is vital to the maintenance of social structure. The bond between charioteer and hero is another highly charged association: traditionally, the sūta, the ‘driver’, is the one to advise the hero as well as to record the deeds of the hero in poetic speech: sūtas were also the poets who sang of the hero’s exploits and maintained his fame and serves as ambassadors. One can observe the importance of this accord between Arjuna and Kṛṣṇa, and its obverse perversion with Karṇa and Śalya. Karṇa, I would aver, is the paramount hero of the Mahābhārata and I would submit that the core epic concludes with his death and the subsequent laments sung for him at the end of the Strī parvan, when Kuntī and Yudhiṣhira perform rites of verbal mourning. Karṇa, unlike Arjuna, is deeply human and thoroughly moral, and he, as the first-born son of Kuntī, is arguably the rightful heir to the kingdom. Arjuna is far more super-natural in his endeavours, visiting the heaven of Indra, combating with daemons, and acquiring magical weaponry. I would propose that the Film open with the scene where the youthful heroes are challenging each other at a trial of weapons: this is where Karṇa makes his entry into the poem and where he first meets Arjuna, and here their counterpoint is founded. Sūrya and Indra, their progenitors, are similarly opposed: as fire and rain.

How the present Film should represent deities poses a problem: what aura or distinction should the possess to distinguish them from heroes, would costume be adequate? I would suggest that, as in the epic itself, their autonomous appearance and disappearance is sufficient, for epic focuses primarily upon the terrestrial world of heroes, an artificial and superhuman realm. The hero and charioteer Kṛṣṇa was played with great aplomb in the long Mahābhārata television series of Chopra: gracious, mischievous and devious, and precise in his wizardry. His facial expressions and manner were well depicted as youthful, handsome, and mercurial.

Regarding the figures of Vyāsa and Nārada—two hyper-conscious semi-divine figures—I think that they can be dropped. The characters and narrative of the Film will supply sufficient metonymy to create a montage of its own. Peter Brook’s use of Vyāsa as literate genius who controlled the poem-film need not be replicated for it only reminds an audience of the artifice of direction: cinema is not theatre, which was essentially the genre of Brook. Perhaps for continuity, the opening and closing scenes could be set in the Naimiṣa forest, where the poets recount to the assembled brahmins the whole of the epic: this is actually how the Mahābhārata opens and closes. The sūta Saṃjaya could perform this role: he is also the immediate confidante of the blind old king Dhṛtarāṣṭra, and he sings—due to his gift of divine eyesight and insight— the events as they occur in the story. In a sense the camera and direction are actually in the place of Vyāsa. Concerning traditional aspects of the Mahābhārata, there are so many versions of the basic poem that the next Film version should certainly cast an eye upon such vernacular non-Sanskritic forms. There are, for instance, many local traditions where an unrequited love relation exists between Karṇa and Draupadī. In several regional tellings, Kuntī is considered to represent the goddess, Devī. Similarly, Rāma Jāmadagnya is a figure in the present epic—and by that I mean the Critical Edition as edited by the Bhandarkar team at Pune—who is a vague character and moves in and out of the narrative, always on the margins. He is arguably the most ancient of the heroes, one who instructs Bhiṣma and Karṇa, and yet he possesses no role in the drama as we have it now. Over the centuries his presence in the story has been diminished to a shadowy role; cinematically, his character might be interesting however, for this very reason.

Some scholars would go so far as to propose—that in its early stages of composition—the Kauravas were the ‘good’ side and that the Pāṇḍavas were the ‘bad’ side; the latter being the ones who perpetrated dishonesty and amoral expedience in order to secure victory. In this view of the epic it is said that the influences were deeply Buddhist. Thus the death of Duryodhana is portrayed not as a triumph over darkness but as a divine release, for when he finally perishes flowers rain down and singing is heard.

From another point of view, it is not difficult to view Yudhiṣṭhira as an ideal Buddhist king, one who is akin to Aśoka of Mauryan times: he is the immaculate Dharmarāja compromised by violence. In Shashi Tharoor’s book, The Great Indian Novel (1989), he is cast as a model after Morarji Desai, pacific and austere. Karṇa in that work is rendered as a Jinnah figure, one who engineers partition, and Bhīṣma is cast as Gandhiji.

Material culture as it concerns this epic is indefinite for the poem is a composite and not unitary work having taken form during a period of at least two thousand years: there are many layers that have accumulated in time. The poem is a synthetic arrangement and refers to no particular place nor historical moment: epic is artificial and integrates many periods and cultures, differing traditions and different vocabularies. One can presume that each geographical region once—hypothetically—possessed its own preliterate epic and its own heroes; these, in time, have become amalgamated into one written work. Thus, the ‘Karṇa epic’ might have belonged to the eastern provinces whilst the ‘Arjuna epic’ derived from a more western area. The recent film Troy is a good example of such synthesis: many texts and myths were drawn into a single narrative to produce a cinematic work of seamless evolution.

The Mahābhārata has grown over the centuries from an Indo-Āryan song—akin to other such epics as the Iliad, the Tain, or Nibelungenlied—into a much larger work which incorporates and represents both late bronze age culture and classical iron age life which was generally pre-urban. I stress the word song, as epic was always a sung medium, sonorous in its recitative declamation, although not melodic.

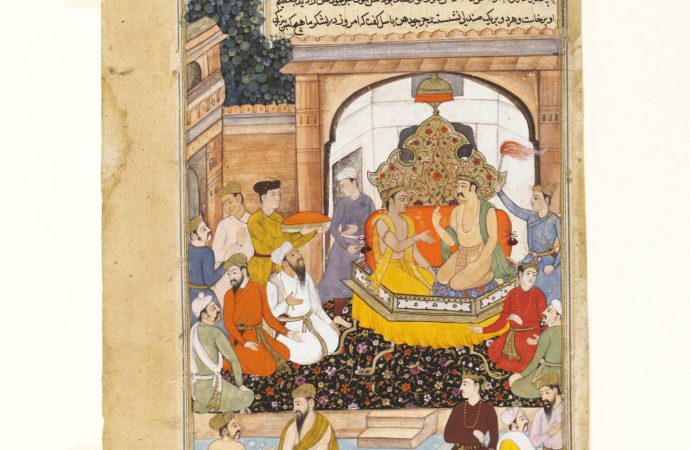

The ninety-two hour television version of Mahābhārata drew its inspiration for representations of material culture—costumes, weaponry, architectural design, and jewellery—from the images of Ajanta and from the figures and reliefs at Sañci and other post-Mauryan sites. The epic makes no demonstration of sculpture, which is curious; unless of course the society which it represents was completely aniconic in its material forms. If one actually looks at the period when the epic first flourished however—which is at least four thousand years ago—the dominant culture then was that of Indus Valley society. This is not IndoĀryan, but a society indigenous to the sub-continent whose culture is mostly lost to us now. There are present-day architectural reconstructions of what a city like Dholavira must have looked like: massive, fabulously wealthy, complex and sophisticated in design and highly organised, with its own well-developed writing system. I would suggest that the present Film draw upon both this kind of culture and the culture represented by Ajanta and Sañci, fusing the two for its sets. Dhṛtarāṣṭra, for instance, could be made to appear as the ‘priest-king’ figure which was excavated at Mohenjo-Daro and is now on display at the National Museum at the National Museum of Pakisthan: this would supply a nice resonance to the footage.

Women heroes are a subject that have not received much attention until recently. I would recommend Mankekar’s book on Screening Culture (1999), as a good example of such a new approach. She shows in detail how the character of Draupadī has been seen by modern women in India as an iconic figure of both suffering and implacable vengeance.

Women in Indo-Āryan epic are always central and are generative of the narrative: they fuel the production of dramatic process. In a pre-literate and pre-monetary society, woman as subjects who were exchanged between families or clans—as brides—were profoundly if not originally creative of social value and order and were arguably primary figures in the creation of social and monetary value.

In the Mahābhārata, the key feminine heroes are the ones who maintain the standards of kṣatriya conduct. In moments of crisis, they are the speakers to remind the heroes as to the nature of human value, as they urge their menfolk to action. Draupadī and Kuntī provide crucial speeches concerning dharma and its interpretation when heroes like Yudhiṣṭhira or Arjuna fail to act correctly. In fact, such women possess a terrific access to verbal skills and are akin to the poets themselves in being adepts at public speaking: they are the voices of truth, who know, transmit, and interpret the dharma appropriate to events.

Draupadī is unique in the poem, for no one experiences the outrage that she endured in the sabhā, nor does any other figure evince such unmitigated wrathfulness. She is closest to Bhīma in intimacy, and he is the one to actually physically and brutally revenge her abnegation. It is Draupadī (and Karṇa) who drive the narrative onward. Her subtlety of manner and emotion are also beautifully displayed in the way that she conducts herself among her five husbands; delicately playing off each one. She can cajole as much as she can threaten bloodshed. Kuntī, as mother-in-law, is the one to direct her sons, and is effectively the senior member of the Pāṇḍava family except in matters of war; Draupadī always defers to her.

Cinema’s attempts at epic began with Fritz Lang’s nineteen-twenty-four version of the Nibelungen, a silent film. If the next Film version of the Epic wishes to portray narrative via action rather than via speech it needs to employ actors who are skilled with visual detail—particularly physiognomy—and gestural implication. Actors who are merely good at mood will not be adequate. The problem with the film Troy was that Brad Pitt was histrionically dull and lacked ability with personal inflection and nuance. As that film relied upon action rather than dialogue to move the drama forward, the production was thus not remarkable.

Likewise, the soundtrack for this present Film must be excellent and able to function as a mimetic agent in itself; much as Satyajit Roy’s soundtracks are vital conveyors of emotion in his films. Lang’s epic film— also a narrative about two contrary sides of a family destroying themselves over the issue of a woman and a kingdom—used a live pianist in the theatre to heighten the emotion and imply shifts in mood that the audience experienced through visual reception. Audial stimulation is thus crucially important for the development of the performance if the script is to be kept minimal: it functions like a character, possessing great emotional efficacy.

The film Gladiator displayed highly authentic material culture, as did the film Alexander; the battle a Gaugamela in this latter film being a truly vivid and accurate representation of warfare in antiquity. The physical aspects of culture in Troy however, were poorly and unevenly researched. The final death scene in Blade Runner—where the hero-replicant Roy perishes—is a scene that I have used many times when teaching the Iliad, an epic similar both in content and tradition to the Mahābhārata. This scene communicates most effectively to a spectating audience the idea of an heroic death and its strangeness and un-natural quality. Heroes are superhuman and sometimes even supernatural, they are not human. Finally, I know that many contemporary cinema-goers were impressed by the production of Tolkien’s Lord Of The Rings, or perhaps by the success of that film, but I would propose that this was not good cinematography. Its achievement was due to the current ideology in the West where evil and good are believed to be presently in contention; and also, the computer generated graphics of Lord Of The Rings stunned audiences who had never before witnessed such a magnitude of visual invention. The film drew upon phantasy and the ‘weird’ and lacked substantial reference, as well as ignoring Tolkien’s extraordinary expertise and knowledge of historical and literary tradition and it was ultimately too hybrid a work.

Despite the implicit violence of Mahābhārata, in classical aesthetic theory the ‘tone’ or rasa of the poem has been considered to be that of śānti, ‘tranquillity’, stabilising the mood and emotion of an audience as the aeon moves towards an ‘iron age’, the kāli yuga, the most imperfect of time scales where a constant condition of grief among humanity at the near impossibility for good conduct and moral rigour obtains. Tranquillity is engaged insofar as the gigantic disorder of battle at Kurukṣetra has been concluded, and katharsis, ‘purgation’ of all the old grief caused by the partition of the Bhārata Kingdom has been effected.

Heroes are figures of transcendence, characters of suffering and of agony; they achieve an ideal through death and the consequent acquisition of fame. The audience of the current Film should depart from the screen with a feeling of release from the tension caused by bheda, ‘partition’, the deluded and absolutely destructive forces of social enmity. Given the resurgence of communal turmoil in the world recently, I would think that such a transcendent sentiment would provide good closure. It is here that the mundane and the poetic—or cinematic—can engage fully.

Heroes exist on the boundaries of human experience; traditionally that frontier is the place of death. Through the poetry of cinema or epic song an audience is able to share in those emotions and perceptions, and so the extent of human life, via art, can become extended into regions only tracked by metaphor. All language is of course simply metaphorical and heroes advance those references, translating the border to the interior. In antiquity heroes were worshipped, just as they are in many parts of India today; what can be described as an heroic religion existed, where such semi-divine figure were the objects of practical devotion and songs of praise. The events in Nineteen Ninety-Two at Ayodhya where communal violence at the birth site of a bronze age hero resulted in many deaths, only sustain such a model of worship.

The Mahābhārata proposes that action is both inevitable and required for kṣatriyas and that human action necessitates judgement, regardless of resolution. The necessity of life lies in this condition, that we are constantly required to make decisions despite the lack of tangible or immediate fruition and despite, due to the immanence of the kali yuga, all possibility of complete moral success. In this imperative the world is posited as dualistic where judgement is primarily founded upon two potential choices: either this or that.

I would propose that the conclusion of the Film occurs after the Sauptika parvan has occurred—the night scene with its gruesome assassinations—and after the horrifyingly and pitiful scenes of the Strī parvan, where the women of both sides patrol the battlefield and sing of their despair and sorrow for the deceased kin and heroes, all who have perished in the internecine struggle caused by bheda, ‘partition’. That point marks the terminus of epic Mahābhārata and the promise of the Dharmarāja’s rule of goodness.

Kevin McGRATH is an associate of the Department of South Asian Studies and poet in residence at Lowell House, Harvard

University. His most recent works include, The Sanskrit Hero (2004), Comedia (2008), Strī (2009), Jaya ( 2011), Supernature (2012),

Eroica and Heroic Kṛṣṇa (2013), and Rāja Yudhiṣṭhira (forthcoming2014).

J u n e TWO THOUSAND & THIRTEEN

Scared Space

Scared Space

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *