In the early summer of 1819, a British hunting party was heading through thick jungle near Aurangabad, in Maharashtra, western India, when the tiger they were tracking disappeared into a deep ravine. Leading the hunters was Captain John Smith, a young cavalry officer from Madras. Beckoning his friends to follow, he tracked the animal down a semi-circular scarp

In the early summer of 1819, a British hunting party was heading through thick jungle near Aurangabad, in Maharashtra, western India, when the tiger they were tracking disappeared into a deep ravine. Leading the hunters was Captain John Smith, a young cavalry officer from Madras. Beckoning his friends to follow, he tracked the animal down a semi-circular scarp of steep basalt, and hopped across the rocky bed of the Wagora river, then made his way up through the bushes at the far side of the amphitheatre of cliffs. Halfway up, Smith stopped in his tracks. The footprints led straight past an opening in the rock face. But the cavity was clearly not a natural cave or a river-cut grotto. Instead, despite the long grass, the all-encroaching creepers and thorny undergrowth, Smith was looking at a manmade facade cut straight into the rockface. The jagged slope had been painstakingly carved away into a perfect portico. It was clearly a work of great sophistication. Equally clearly, it had been abandoned for centuries.

A few minutes later, the party made their way gingerly inside, as Smith held aloft a torch of burning dried grass and his companions clutched their muskets. A long hall led straight into the rock, flanked on either side by 39 octagonal pillars. At the end rose the circular dome of a perfect Buddhist stupa carved, like everything else, out of the slope of the mountain.

All over the walls, the officers could see through the gloom the shadowy outlines of ancient murals. On the pillars were figures of orange- and yellow-robed monks with green haloes standing on blue lotuses, while on the rock walls facing on to the side aisles were long panels of painting filled with elaborate crowd scenes, rather as if a painted scroll had been rolled out along the wall of the apse. In the light of the flickering flame the officers crunched over a human skeleton and other debris dragged into the cave by generations of predators and scavengers. The party advanced until they reached a pillar at the far end of the hall, next to the stupa. There Smith got out his hunting knife and inscribed over the body of a Bodhisattva (a previous incarnation of the Buddha) the words: “John Smith, 28th cavalry, 28 April 1819.”

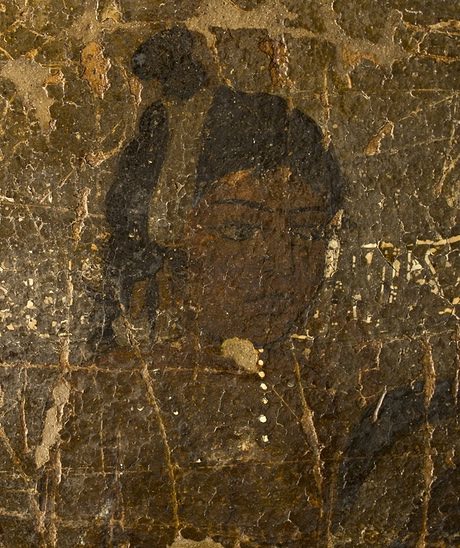

Otherworldly beauty … A mural in cave 10 of the Ajanta caves. Photograph: Prasad Pawar

In the decades to come, first other hunting parties, then later groups of Orientalists, archaeologists and Indologists followed in Smith’s footsteps through the jungle to Ajanta as word spread that in this most remote spot lay 31 caves that collectively amounted to one of the great wonders of the ancient world. The walls told the Jataka stories of the lives of the Buddha in images of such extraordinary elegance and grace that they clearly represented a fragment of a lost golden age of Indian painting. They were utterly lovely – but they were also utterly alone: with a very few fragmentary exceptions, there is almost nothing else surviving from the ancient Indian past to compare them to. The murals of Ajanta are now recognised as some of the greatest art produced by humankind in any century, as well as the finest picture gallery to survive from any ancient civilisation. Even today, the colours glow with a brilliant intensity: topaz-dark, lizard green, lotus-blue.

❦

From almost the beginning, scholars working on the site came to the realisation that there were two quite distinct phases of work at Ajanta. The cave that Smith first walked into, later named cave 10, lay in the centre of the cliff face; it and the five others flanking it were datable by inscription to the first or second century BC.

However most of the Ajanta caves, and almost all the murals, date from nearly 600 years later, during a second phase of construction. This was at the height of India’s golden age, when in the Gangetic plain, the fifth-century Gupta dynasty was filling their capital of Kannauj with some of the greatest masterpieces of Indian sculpture, and when Kalidasa was writing his great play, The Cloud-Messenger.

From this period date the rich picture cycles of wall painting in caves one and two. Here among handsome princes and bare-chested nobles, princesses with tiaras of jasmine languish love-lorn on swings and couches, while narrow-waisted dancing girls of extraordinary sensuousness, dressed only in their jewels and girdles, perform beside lotus ponds. Nearby are painted very different images of stark ascetic renunciation – a shaven-headed orange-robed monk lost in meditation, a hermit seeking salvation or a group of wizened devotees straining to hear the words of their teacher. Dominating everything are portraits of bodhisattvas of otherworldly beauty, elegance and compassion, eyes half-closed, swaying on the threshold of enlightenment, caught in what the great historian of Indian art, Stella Kramrisch, wonderfully described as “a gale of stillness”.

Striking … the Ajanta cave murals. Photograph: Prasad Pawar

Such was the celebrity of these fifth-century masterworks that most scholars, and almost all modern accounts of the Ajanta caves, have all but ignored the earlier picture cycles. These paintings were not only more fragmentary, they were also more smoke-blackened than the almost pristine later murals, and perhaps for this reason seemed to invite the attention of early graffiti artists and tourists who wanted to leave a record of their visit.

By the time the Nizam of Hyderabad sent the leading art historian of his state, Ghulam Yazdani, to produce the first photographic survey of the murals in the late 1920s, the murals of caves nine and 10 had already been irreparably damaged. The Nizam also sent two Italian conservationists to help restore them. Unfortunately their efforts only obscured the murals further: they coated the pigments with a thick layer of unbleached shellac that sat on top of at least two existing Victorian layers of varnish. The shellac attracted grime, dust and bat dung, and quickly oxidised to a dark reddish brown that totally obscured the images from both travellers and scholars. Less than a century after being rediscovered by a British shooting party in 1819, the figures of caves nine and 10 had been lost again. For the rest of the 20th century they remained effectively hidden, invisible to the naked eye, forgotten by all.

Then in 1999, Rajdeo Singh, the Archaeological Survey of India’s (ASI) chief of conservation and head of science at Aurangabad, began work on the restoration of these murals. Manager Singh, as he is always known, had been in charge of conserving the paintings of Ajanta for a number of years, but the work in caves nine and 10 was, he knew, especially difficult, and of the greatest importance: “The paintings were so fragile that in some places there was a great fear even to touch them with the hand,” he wrote later. “At some places the pigment was found completely detached from the ground plaster and stone surface.”

However a painstaking restoration of the paintings from 1999 onwards using infrared light, micro-emulsion and cutting-edge Japanese conservation technology succeeded in removing 75% of the layers of shellac, hard soot and grime from 10 sq m of the murals. “Particular care and precautions were taken not to alter even a grain of pigment,” he wrote.

Manager Singh’s work revealed for the first time since the 1920s the images that are now on open display. Remarkably for so famous a site – Ajanta is one of a handful of world heritage sites in India, attracting 5,000 visitors a day – their wall paintings have never before been properly photographed.

The Ajanta caves. Photograph: Getty

I stumbled across them on a visit to the caves in March. The ASI does not have much of a tradition of public outreach, and even internally there is perhaps little recognition of what Manager Singh has achieved and uncovered. For his work is nothing short of a revelation: Singh has uncovered the oldest paintings of Indian faces – with the exception of a few prehistorical pictograms of stick men and animals left by paleolithic hunters in the wilds of Madhya Pradesh. They are also the oldest Buddhist paintings in existence, dating from only 300 years after the death of the Buddha.

More exciting still, this earliest phase of work is not just very old, but very fine indeed and painted in a quite different style, and using markedly different techniques to that used in the rest of Ajanta. The murals of caves nine and 10 represent nothing less than the birth of Indian painting.

❦

The extreme antiquity of the caves is clear, though their exact dates remain elusive: from the paleographic evidence they can be securely dated to between the second century BC and the first century AD, but most scholars believe that between 90-70BC is the most likely period of construction. This meant they were excavated shortly after the collapse of Ashoka’s great Mauryan empire, which once stretched from Kandahar to the Vindyas. They are roughly contemporary with the spectacular Buddhist stupas and gateways at Sanchi and Bharhut, built during a period of political disruption across India but also one of great artistic and intellectual ferment.

Inscriptions in cave 10 record the many small patrons of these masterworks, like sponsorship tags on television today. One mentions a Kanhaka of Bahada, presumably a nobleman, others monks named Dharmadeva and Sikhabhadra, the latter “in honour of his mother and father”. This was a period not of royal but of community patronage, and appropriately the murals were a crowded, vibrant narrative art, teeming with people and alive with drama.

Cave 10 contains a supreme treasure that has only recently been identified: fragments of the oldest surviving painting of the life of the Buddha and an image of the first sermon at Sarnath. Next to the latter lies a depiction of the legend of Udayana, a tale of two rival queens, one virtuous and one evil. The most dramatic, and best preserved scenes however show two Jataka stories: the “Shyama Jataka” is about a forest dweller who was fatally hit by the poisoned arrow of the king of Varanasi. Next to it is the “Chaddanta Jataka“, which tells of a virtuous six-tusked elephant that is killed at the instigation of a jealous and vindictive queen.

In illustrating these stories, the artists of Ajanta open a window on to an age about which we know little. We see the costumes of this very early period: the king of Varanasi, for example, wears a white cotton tunic of strikingly central Asian appearance, wrapped around the waist with a cummerbund, while on his head he wears a turban. He has a bow and a full quiver of arrows. His guards are bare-chested and are armed with spears and bell-shaped shields decorated with half-moons and shining suns. The turbans of the different ranks are shown with great care and seem to be an important indicator of status, the different materials – some with red or gold stripes, others pure white – and the different styles of wrapping are delineated with the greatest care.

Much about the clothing is identical to that worn by the sculptures at gateways of the Great Stupa at Sanchi, and there is the same interest in detail, yet the style is in feeling and temper subtly different. In Sanchi, the images are animated with a wonderful joie de vivre. Here there is a sadness in the programme of painting, which is concerned with justice, peace and non-violence: one image tells of a war breaking out over the Buddha’s relics – something that went totally against the grain of everything he taught.

Two kings from oldest surviving painting of the Life of the Buddha. Photograph: Prasad Pawar

There is also something very different in the style of these faces. Their physiognomy and the world in which they are depicted may be utterly Indian, yet the artist’s long, bold brushstrokes, the use of perspective and three-quarter profiles, the play of light across the large brown eyes and cheekbones, and the technical aspects of the work with its choice of pigments and use of lime mortar all show a hint of Hellenistic influence.

This is hardly a surprise: after all, at this period Indo-Greek kings controlled as far south as the Punjab and were deeply integrated into the Indian world. This intimacy, classicism and striking realism, combined with the haunting wistfulness of the features of these faces, is not a million miles away from the distant, melancholy world of the later first century AD encaustic wax mummy portraits from the Fayum region of Greco-Egyptian Egypt, which were also the products of the Hellenisation of the east. In both, we are in a world so lifelike that even today, even in reproduction, they can still make you gasp as you find yourself staring eyeball to eyeball with a silently watching soldier who could have fought the Bactrian Greeks, or a monk who may have seen the sculptures at Sanchi being carved.

So realistic are the faces of the people depicted that you feel these have to be portraits of real individuals. There is none of the idealisation or otherworldliness you see in the later images of the bodhisattvas. Instead there is something deeply hypnotic about the soundless stare of these silent, often uncertain, Satavahana faces. Their fleeting expressions are frozen, startled, as if suddenly surprised by the king’s decision to loose his arrow or by the nobility of the great elephant breaking through the trees. The viewer peers at these figures trying to catch some hint of the upheavals they witnessed and the strange sights they saw in ancient India. But the smooth, clean humane Indo-Hellenistic faces stare us down.

Perhaps the most disconcerting thing about the people in these murals is that they appear so familiar. Two thousand years after they were painted these faces convey with penetrating immediacy the character of the different sitters: the alert guard, the king caught in the excitement of the hunt, the obedient son fetching water. Indeed, so contemporary are the features that you have to keep reminding yourself that these sitters are not from our world, they are depictions of a court that vanished from these now bare hills more than two millennia ago.

Yet these are self-evidently the same people who inhabit western India today: looking at these images you cannot help but feel the great distance of time separating them from us; and yet we find in their eyes an emotional immediacy that is at once comprehensible. While the glass coverings were being removed to allow the photography for this piece, the guards joked among themselves about which painted figure looked most like which guard. The women on the cave walls wear the same bangles that the Banjara tribes of these hills still stack along their forearms, and their dupattas are decorated with fringes of taarkaam or Paithani still popular in Maharastra today, as are the fish-scale kham textiles that clothe the hunters in the Shyam Jataka. It is eerie to stare into the eyes of men and women who died more than 2,000 years ago; but odder still to feel that their faces are somehow reassuringly recognisable.

1 comment Scared Space

Scared Space

1 Comment

Satish Madhiwalla

January 17, 2024, 2:43 pmAmazing realism, intricate compositions, sinuous lines and modulated colours of the paintings at Ajanta,

REPLYcan by no stretch of the imagination be labelled as "the Birth of Indian Art". They obviously are the result of decades if not centuries of development whose record has been obliterated by many invasions of people from West of India, Greeks, Kushans, Scythians etc; with differing cultures and beliefs.

It is almost a miracle that these paintings survived, as they are in caves away from cities in forested area.